Artist Cynthia Riordan spends some quiet time in the Los Altos Civic Center Apricot Orchard. The Orchard is a City Historic Landmark.

I thought you might enjoy taking a walk at your leisure through the Los Altos Civic Center Apricot Orchard. I researched and wrote it last summer and have led it myself half-a-dozen times. But now I've posted it here so you can call it up on your device and take it yourself. Or you can relax at home and take it as an armchair tour!

Orchard Entrepreneurs Walk

by Robin Chapman Location I: Orchard-side door of the Los Altos Library (face the orchard with the library at your back), 13 S. San Antonio Road, Los Altos:

Welcome to one of the oldest continuously operating apricot orchards remaining in Santa Clara Valley, a City of Los Altos Historic Landmark.

What is this Orchard Doing Here?

Gilbert Smith in the hills above Los Altos in the early 20th century.

Smith is the orchardist who planted the original orchard that today surrounds the Los Altos Civic Center. Photo from California Apricots: The Lost Orchards of Silicon Valley by Robin Chapman (History Press 2013)

The orchard you see here was planted by a man named Gilbert Smith in 1901. Smith rode his bicycle back and forth to Stanford University where he worked as a carpenter so his siblings could go there to school. After studying briefly there himself, he quit and bought his first five acres right here and planted his first apricot trees. Eventually he owned 15 acres in and around this site.

Location II: Use the sidewalk to turn to your left and walk to San Antonio Road, the busy roadway adjacent to the Orchard. Look up at the hills above our village and then down (to your right) toward San Francisco Bay. As you face San Antonio Road, City Hall will be on your right.

If you were to stand at the stop of Skyline Boulevard and look down on this land, you would see San Antonio Road goes down to the edge of San Francisco Bay (you used to be able to see all the way to the Bay from here, but today there are too many trees and buildings and cars and people in the way). The Ohlone were probably the first to forge these paths as they traveled from Bay to mountains and back, hunting and gathering during the seasons.

In the 19thand 20thcenturies, orchardists needed land on direct routes like this one, which crosses El Camino Real, because El Camino was the main highway that linked the busy cities of San Francisco and San Jose. Horses and wagons full of heavy loads of fruit needed to be near main roads. Once automobiles came along, El Camino Real, in 1912, became the first paved highway in Northern California. Entrepreneurs need good transportation for their products to succeed.

Climate can also influence business. The weather is so good here, Gilbert Smith pitched a tent to live on this land while he built his house and cultivated his orchard. His house was completed in 1905 and you will see it at the end of this walk.

Location III: Use the sidewalk to walk along San Antonio Road to the entrance to City Hall along San Antonio Road at 1 North San Antionio Road, Los Altos, and step into the Orchard there and stand in the shade.

California Agriculture and the First Spanish-Speaking Immigrants

A vintage postcard of Mission Santa Clara from California Apricots: The Lost Orchards of Silicon Valley, (History Press 2013).

Apricots are not native to California. Scientists believe their origins are in China. Through the centuries they moved with traders along the Silk Road to Central Asia, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, where they thrived. The Romans discovered them in Armenia where they named them prunus Armeniaca, or the “prune out of Armenia” and that is their scientific or binomial name today.

Researchers believe the first Spanish-speaking immigrants brought apricot trees to California when they came in 1769 on their 1000-mile journey from Mexico. They brought these trees because the fruit reminded them of their homes in far away Spain.

Father Junipero Serra came from the Spanish island of Mallorca, which is still today noted for its cultivation of apricots, so it isn’t surprising he brought this fruit with him. We know apricot trees were here as early as 1802 because English explorer George Vancouver saw them in the gardens at Mission San José in (what became) Fremont and at Mission Santa Clara on this side of the Bay. Coastal California, like Spain, is warm and mild and the trees thrived here. The Bancroft Library in Berkeley has an 1880 interview with an Ohlone in Santa Cruz who said his father told him he remembered the fruit trees coming to the missions in oak barrels filled with soil to protect the roots of the seedlings.

There were only a few thousand Spanish-speaking immigrants in California during those early days. When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, the missions and their orchards were secularized and many were abandoned. But fruit trees have a long life and thirty years later, during the California Gold Rush that was important. Three hundred thousand people came to California to seek their fortunes, and there was no commercial agriculture in place to feed them.

That’s when historian Edward Wickson of U.C. Berkeley says some of the farm boys who had come here to seek gold, noticed the fruit growing in the mission gardens. They harvested the fruit from Mission Santa Clara and Mission San José (probably without permission!) and sold it in San Francisco and got the idea to make their fortunes as growers. Their gold was the gold of an innovative idea.

They showed the entrepreneurial spirit that would dominate this valley on into the 21stcentury.

Location IV: Walk into the parking lot between City Hall and the Los Altos Youth Center (LAYC) and standing on the asphalt, face the Orchard.

Other Innovations Helped Make the Orchards Thrive

It is impossible to understate the importance of the First Transcontinental Railroad to agriculture in California. People said it was an impossible task. But through deserts, plains and into the Sierras, America--and many immigrant workers--worked to make it possible. Vintage postcard from of Historic Bay Area Visionaries by Robin Chapman (History Press 2018).

California growers had a problem, once they got rolling after the Gold Rush. They could bring trees here by ship—for a seedling can survive a long journey—but their fruit would spoil in the time it took to travel from here to New York by ship or wagon. First, they needed a way to preserve the fruit. Then, they needed better transportation.

During the Civil War, industry perfected the mass production of canning in order to feed the millions of Americans in uniform during that terrible war. After the war was over, people who wanted to make a profit brought the cannery business to the Santa Clara Valley.

There was another way growers could preserve their fruit; and that was by drying it. At first, valley entrepreneurs used machines called dehydrators, but they are expensive machines to buy; they require fuel (which also costs money); and the process is time consuming. One year there was a shortage of dehydrators and somebody looked up at the California sun. That’s when the orchard entrepreneurs revived an ancient practice that was then perfected in California: the sun drying of fruit. Used by the ancient Egyptians, its first big commercial use in human history was right here in the Santa Clara Valley.

Finally: there was the issue of transport. How to get goods to market in the Eastern U.S. and the world? American railroad entrepreneurs solved that problem.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed the bills into law that created the First Transcontinental Railroad—the longest railroad in the world at that time, going over the highest mountains, designed to connect America from coast to coast. Nothing like it had ever been done before. When it was completed in 1869, the tools were in place for California growers, in the Santa Clara Valley, to create a business that could preserve its products and transport them around the world. The orchard you see here is a landmark to these business innovations.

Location V: Walk around the playground and stand on the sidewalk between the Los Altos Youth Center and Los Altos City Hall (there is some shade from the roof here too). Who were these Orchardists? It turns out, Gilbert Smith who owned this orchard, was typical.

Family Orchards Dominated the Santa Clara Valley

Agriculture is hard work. But in the Santa Clara Valley it was also very beautiful.

Vintage postcard from California Apricots (History Press 2013).

This orchard you see here was one small family business among the many that dominated the Santa Clara Valley during the peak of the orchard business here between 1870 and 1970. Big Ag, as it is known today in California, did not exist then. In fact, throughout the history of mankind, farming of all kinds was done almost entirely for subsistence—first to feed the family, with only the surplus going to market.

California fruit entrepreneurs turned that on its head. Here in the Santa Clara Valley they grew primarily for market keeping only the surplus for their own use. This is why California farmers are not called farmers—they have always been called “growers” because they grow things as a business and always have. Orchardists discovered they could earn enough from a 10 or 15-acre orchard to feed a family and send their kids to college. By the turn of the 20th century there were 25,000 growers with their own orchards right here in the Santa Clara Valley. Nearly half the valley’s acreage was in agriculture. There were 85 canneries at the peak of the agricultural era, 23 dried fruit processing plans, 25 frozen fruit operations, and 85 fruit and vegetable packing houses. This valley in aggregate, was the largest commercial fruit orchard the world had ever seen.

The preserved fruit could be shipped by rail all over the United States. From railheads on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts it could then be sent by steamship around the world. Canned and dried fruit from the Santa Clara Valley helped feed Allied soldiers in World War I and World War II and improved the diets of people worldwide. In the early 1930s, one third of the processed fruit in this valley went to Germany, until Adolph Hitler came to power in 1933 and cancelled the contracts.

Californians in the Santa Clara Valley had created the largest fruit business in the world.

Location VI: Walk on the sidewalk in the center of the Orchard to City Hall and stand in the shade of the building there and turn to face the orchard.

How Did a Collection of Growers Grow Their Businesses?

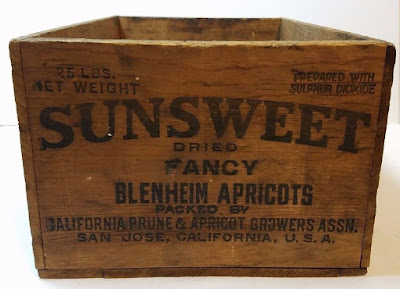

Sunsweet (which is still operating today), was one of the innovative business models created in the Santa Clara Valley.

Mr. Smith’s orchard here in Los Altos was one of thousands of independently-owned orchards in the Santa Clara Valley. How does a collection of 25,000 individual businesses like that, growing the same products, competing with one another, make a profit? Who sells their fruit to the canneries? Who sets the price? Must each grower make a deal with every grocery store, chain, or distributor? That would be chaotic.

Growers—who also had to be entrepreneurs—tried many systems. They established growers' cooperatives in this valley to sell and market their fruit. Some succeeded and some did not. One of the most successful was established in San Jose in 1917. It was called the California Prune and Apricot Growers Association and it is still in business today. You’ve probably heard of it. It is called Sunsweet.

Some growers established relationships with local canneries and signed their own contracts to one or the other. One of the most successful cannery businesses in the Valley was owned by a Chinese immigrant called Thomas Foon Chew who with his father founded Bayside Cannery in Alviso and eventually had operations in Palo Alto, Alviso, Monterey (where he canned fish) and on the Sacramento River. He was a millionaire when he died in 1931.

Across the street from Los Altos City Hall is the fruit stand called DeMartini Orchard established in 1932 for the DeMartini family's own orchard products. Though Mr. Smith sold his apricots through various outlets, today you can buy the Blenheim apricots from the Civic Center at DeMartini Orchard during the season. Fruit stands were another way these entrepreneurs made a profit. In addition to DeMartini, C.J. Olson Cherries did this in Sunnyvale (though their store is now closed) and Andy’s Orchard in Morgan Hill still is in operation. But fresh fruit and fruit stands were always the smallest part of these growers’ business. Millions of pounds of fruit from this valley was more likely to be traded on the commodities market in Chicago than sold at a fruit stand along a roadway.

Location VII: In front of the Library’s back door again, note irrigation pipes as we pass them. Apricots need one-acre-foot of water per tree per season in climates that have no summer rain (as we do not).

How Did City Hall End up In the Middle of An Orchard?

That's my father standing in the middle of the lot he bought in Los Altos in 1947.

It was a newly subdivided apricot orchard off Covington Road. He died in 2010.

Photo courtesy of Robin Chapman.

For the first half of the 20th century Mr. Smith’s orchard was in Los Altos, but Los Altos was only an address—it was not an incorporated city. The population was low and it was mostly rural. That began to change after World War II, right about the time my own parents moved to the region. The people of that generation had seen the world during WW II and California looked pretty good to them. That’s a picture of my father standing in the apricot orchard on the ¼ acre lot he bought here to build his first home for his family. The population of this little town began to grow after World War II. So, in 1952 Los Altos residents voted to incorporate. Los Altos was a village with a small-town atmosphere and big, quarter-acre lots. Housing developments were beginning to sprout up in Mountain View, so Los Altos incorporated as the first mayor said: “To keep from becoming a city.” (Good luck with that in California!)

To keep the semi-rural feel of Los Altos, the little village vowed to put in as few street lights as possible in the neighborhoods and only install sidewalks when absolutely necessary. These two features of Los Altos (while challenging for nighttime strolls) turned out to be very good for the environment.

Yes, But About Those Trees Around City Hall …

Vintage postcard view of the Santa Clara Valley from Historic Bay Area Visionaries by Robin Chapman (History Press 2018)

After incorporation, Los Altos needed a City Hall. In February 1954, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright was visiting Stanford University just at the time Los Altos was looking for land on which to build its first city buildings. George Estill Senior, one of our first council members and mayors, knew the famous architect and asked him to come to Los Altos and look at possible City Hall sites. Frank Lloyd Wright fell in love with this spot for, “its beauty and its heritage” (as city leaders later told the Los Altos Town Crier newspaper) and urged Los Altos to put its City Hall right here.

Wright probably hoped to be the architect for it. But he was in his 80s and time was running out. Los Altos was new and had no money. In the end, the Civic Center was designed by a Palo Alto man called Carol Rankin at Ernest J. Krump Associates, the same firm that designed Foothill College.

But I’m getting ahead of myself: First the city had to buy Smith's property, and Gilbert Smith negotiated a remarkable deal. Los Altos agreed: 1) to remove only the trees as necessary for construction; 2) to give Smith a life interest in the fruit of the trees that remained after construction and finally; 3) to keep an apricot orchard here in perpetuity. For his part, Gilbert Smith and his wife Margaret agreed to deed their home to the city when they died to be used for history and education. Quite a deal. Still when the city pulled out the first trees for City Hall—city workers said Gilbert Smith cried.

Gilbert Smith died in 1966 and his wife Margaret died in 1973. Their home became our city’s first museum. He proved to be an able entrepreneur. He was not only able to keep his orchard operating after he sold it, he was able to keep it operating after he died!

Location VIII: Walk from the library, along the edge of the Orchard toward the Los Altos History Museum and note the shaded and shingled house across the roadway. Stop there at the edge of the Orchard and admire it. That is Gilbert Smith’s house. After his death it served as the first Los Altos History Museum.

The Orchard Today

The J. Gilbert Smith House is open for tours Thursday through Sunday, noon to 4:00 p.m.

But you must ask next door at the Museum for a docent led tour. Photo from Historic Bay Area Visionaries (History Press 2018).

The Orchard at the Los Altos Civic Center. © Robin Chapman

Mr. Smith’s orchard began to be cited as an historic landmark by the county as early as 1962. In 1970, the city council voted to preserve it. It was given landmark status by the city in 1977, again in 1978, and became an official City Historic Landmark under CEQA (the California Environmental Quality Act) in 1981 and is now, also, an official California Point of Historical Interest. It is the only Historic Landmark that is not a building but is, instead, an agricultural space. And it is the only City Historic Landmark that does not carry a sign or its landmark plaque.

Parks Department records show it is 2.84 acres today with spaces for 444 trees: a size set by law in 1991.

As the orchard businesses were replaced by technology after World War II, many of the orchard entrepreneurs leveraged their land to join enterprises in real estate, development, and other startups. The Olson family of Sunnyvale did that, the Pavlina family of Los Altos did that, and so did the Vidovich family of Los Altos Hills among many others. That’s the practical way orchards became connected to a new generation of innovators after 1972 (the year technology's profits passed agriculture's profits in the Valley). Land was capital and that capital was invested right here in California’s future.

The orchards also have an emotional connection to the new technologies. After David Packard of Hewlett Packard took his company public, and he had wealth to invest, he cultivated 60 acres of apricot trees in Los Altos Hills. When he died he left those orchards to his foundation, which operates them today. Steve Jobs in the 1990s bought the house next door to his in Palo Alto and tore it down—not to build a bigger house, but to plant an apricot orchard there. Jobs told an historian at the Smithsonian Institution that he recalled moving to the Santa Clara Valley from San Francisco when he was five years old: “Silicon Valley for the most part at that time was still orchards,” he said. “Apricot orchards and prune orchards—and it was really paradise.”

It still is today. Thank you for taking this walk through our history and a small piece of our paradise.

No comments:

Post a Comment